by Killing Thousands of Sharks?

Article by Prof. Jessica Meeuwig, The University of Western Australia

(originally posted on The Conversation - 21 February 2014)

One of the most common justifications for Western Australia’s shark cull is the longstanding use of baited hooks - or drum lines - in regions such as Queensland. Two key questions need answering. First, is there clear evidence that drum lines reduce the number of human fatalities from sharks? And second, what is their cost in terms of killing marine wildlife?

One of the most common justifications for Western Australia’s shark cull is the longstanding use of baited hooks - or drum lines - in regions such as Queensland. Two key questions need answering. First, is there clear evidence that drum lines reduce the number of human fatalities from sharks? And second, what is their cost in terms of killing marine wildlife?

To that end, I have analysed publicly available figures for human fatalities in Queensland with data on the program’s shark catch, to provide an assessment of its effectiveness. Over more than half a century, the program has taken a large toll on wildlife, while any increase in human safety has been equivocal at best.

The Queensland cull

As of December 2013, there were 369 drum lines and 30 nets deployed off the Queensland coast, mostly near swimming beaches. The program has grown steadily since it began in April 1962 with the deployment of 24 drum lines on the Gold Coast; it now extends to Cairns across a total of ten regional areas.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Drum lines and shark catches

Between 1853 and 2013 there were at least 71 human fatalities due to unprovoked shark attacks in Queensland, with the majority of these attributed to tiger sharks and only a single fatality to white sharks.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Queensland shark fatalities at beaches with drum lines

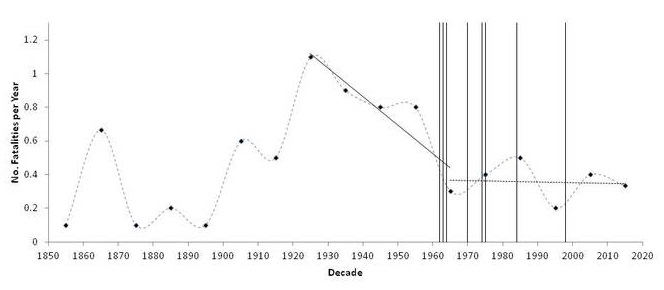

During these 160 years, the average fatality rate varied. From 1850 to 1910 it was 0.32 fatalities per year, but then a spike in fatalities in the 1920s saw the average increase to 1.1 per year. After that, the rate of fatal attacks generally declined, falling to a low of 0.2 per year in the 1990s. Since 1962, when the drum line program began, the fatality rate has averaged 0.37 per year, a number not significantly different than that previous to the 1920s.

Mean number of fatalities per year (averaged by decade) through time. Vertical line indicate introduction of drum lines. Dotted lines show general declining trend from 1920s to 1970 and the steady trend post 1970.

Mean number of fatalities per year (averaged by decade) through time. Vertical line indicate introduction of drum lines. Dotted lines show general declining trend from 1920s to 1970 and the steady trend post 1970.

The graph shows that there has been a significant decline in Queensland’s rate of shark attack fatalities but that it started 40 years before drum lines were first deployed. There has been no further reduction in fatalities since the program began, despite half a century of increasing drum line deployments.

Note also that these statistics include fatalities in areas with and without drum lines. Of the 71 reported Queensland fatalities, 50 were in areas such as the outer Great Barrier Reef or Moreton Bay, where no drum lines (or nets) are present.

In areas without drum lines, the average fatality rate, calculated on a decadal basis, was 0.34 per year before 1970 (used as a cut off point given the 1960s saw only relatively few drum limes compared to the full program now implemented) and 0.24 afterwards. Even without drum lines, fatalities declined by 28% between these two periods.

In areas with drum lines, fatality rates fell from 0.05 to 0.02 fatalities per year pre- and post installation of the drum lines, a decline of 70%. This suggests that the fatality rate fell more rapidly in areas with drum lines than those without.

However, this result is deceptive. Of the seven locations with drum lines only (no nets), six had recorded only a single fatal attack prior to the installation of drum lines (ranging from 5 to 95 years before the lines were deployed). Only Kissing Point had a history of more than one fatality (in 1916, 1933 and 1955) before drum lines were installed in 1965. So for the most part, this apparently rapid decline represents the difference between one attack that could have occurred up to 95 years ago, and no attacks today at a limited number of sites.

This highlights the problems we face when trying to understand patterns in shark attacks and the effect of mitigation programs – fatalities are such rare events that differentiating between random coincidence and underlying patterns is fraught with difficulty.

What is the cost to marine life?

In contrast to their contribution to human safety, one thing we can be certain of is drum lines' ecological cost. The most recent available data show that Queensland caught some 6250 sharks on drum lines between 2001 and 2013, or an average of 480 animals per year.

This catch included 35 different species, the most common being tiger sharks (41%), bull sharks (17%) and black tip reef whalers (12%). White sharks, although considered a key target species in WA, represent less than 1% of the Queensland catch with about five caught per year.

Only 3% of the sharks killed on Queensland drum lines are considered not to be at conservation risk. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, four species, representing 5.2% of the catch, are “endangered”; nine species (9.6% of the catch) are "vulnerable”; and 15 species (80.6%) are classed as “near threatened”. Only six species (1%) are considered to be of “least concern”, while one species (2%) is considered “data deficient”.

Sharks longer than 3 metres have been classified as dangerous to humans, at least in WA. Yet only 11% of the animals culled in Queensland were larger than this – the average size of sharks captured on the drum lines was 1.9 metres.

In terms of reproductive maturity, all of the white sharks and most of the tiger and bull sharks that were caught were juveniles. As a key strategy for shark recovery is the protection of large breeding individuals, this may appear a reasonable outcome. But equally, juvenile deaths will ultimately reduce the future population of breeding adults.

What have we learned?

Based on this analysis, we can conclude that:

Shark-related fatalities in Queensland have declined in both areas with and without drum lines, with the steepest rates of decline before their installation.

The effectiveness of drum lines is difficult to evaluate, as the rates of attacks before and after their deployment are both very low. Moreover, 83% of drum lines are deployed at locations where a fatal attack has never occurred.

The ecological cost of drum lines is high, with 97% of sharks caught since 2001 considered to be at some level of conservation risk, and 89% caught in areas where no fatalities have occurred.

Drum lines: a blunt tool

It could be argued that the drum line program in Queensland is justified simply because it may remove sharks from popular areas. However, it is a very blunt tool and ignores the important ecological roles that sharks play in our oceans.

Moreover, its success in reducing human fatalities is hard to validate. The decreases may simply reflect broader declines in shark populations, driving down encounter rates despite the increased human presence in the ocean. Or they may simply be random.

There are non-lethal techniques that can potentially achieve much better outcomes. Humans and sharks alike could benefit from an approach that embraces new ideas, rather than one that has produced little measurable effect in half a century, other than to kill threatened species.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

-----------------------------------------------

Leave your questions below and the team will try and answer as many

as possible.

Other Interesting Articles:

Disclaimer

Support Our Sharks posts articles and material

prepared by other organisations and individuals not affiliated with

Support Our Sharks for educational purposes. Support Our Sharks does not

necessarily agree with the opinions expressed in such material. Support

Our Sharks also provides links from this site to the websites of

featured news articles above for informational purposes only. The links

do not imply an endorsement by Support Our Sharks of these articles or

the content of their respective web pages.